A preview of Glories of Venice: A Celebration of Rare Cellos, Sunday 25th November at the Royal Academy of Music, Dukes Hall 5pm and 7pm

A Celebration of Rare Cellos

Sponsored by Brompton’s Fine and Rare Instrument

Justin Pearson describes the encounter:

The encounter took place in Charles Beare’s beautifully restored barn in Kent, home to the family business Beare Violins Ltd. A heavy, black antique wooden cello case stood by the wall. Inside, was the reason for our visit: a cello fashioned by the eighteenth century Venetian maker, Santo Serafin, a craftsman who switched from painting portraits to making stringed instruments with comparable artistry and keen eye for detail. Serafin made only a handful of cellos, some of them small, but his full-sized instruments are legendary in terms of quality of tone production and aesthetic appeal.

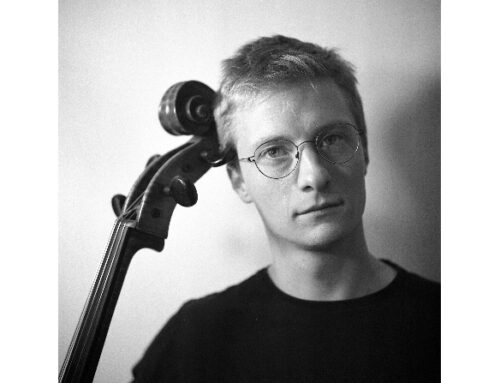

Skeku had travelled to play this cello to see if he might perform on it at the upcoming concert in London on November 25, “Glories of Venice”. The event takes place at the Royal Academy of Music, where, despite his rapidly ascending high-profile career, Sheku is still a student.

Charles opened the “coffin” case revealing the cello, still preserved in mint condition. Peter Horner, the renowned auction expert had described the instrument to me as “the most beautiful cello I have ever seen, the jewel of the Beare collection”. The front boasted a striking, strong grain; the back and ribs exhibited a glorious flame of symmetrical figuration and dark amber colour. The elegance of the ‘f’ holes, the meticulous care accorded to every detail, are the characteristics of this luthier’s craftsmanship.

“I hope you like it”, said Beare quietly. “Pierre Fournier did”.

No pressure then.

Sheku started to feel his way around this unfamiliar cello. Most cellists I hear trying instruments will start by playing the opening of a concerto, a sonata or solo Bach. Sheku, however, methodically worked his way up and down each string, bowing slowly to find all points where he could bring out the colours for which he searched; spending a while bowing near the bridge, then over the fingerboard, fingering right in to the highest positions, more often piano than forte.

Sheku’s exploration of the Serafin was mesmerizing. He appeared lost in his own sound world, apparently devoid of self-consciousness, communicating a direct connection between himself and music. Beare sat watching, unhurried. Later, he was to remark to me that he found Sheku’s individual voice “a little akin to du Pré in its individuality, its intimacy.”

Beare suggested that Skeku might wish to try a different bow, and a priceless Tourte was brought for him to try. Though the sound was more concentrated and tone quality more sweet with this stunning bow, Sheku reverted to using his own bow. “One new thing at a time”, he wisely remarked, displaying a maturity beyond his years.

After an hour of finding the centre of the sound, Sheku finally launched into the prelude of a Bach suite. It was a memorable moment. I was deeply impressed by the artistry, dexterity and gracefulness of his performance. His bow strokes were elegant, his performance informed by period sensibility whilst projecting and communicating.

Beare caught my eye and we nodded in shared admiration. This young man had something special.

“Well, Sheku, will you be happy to perform on the cello at the concert?” asked Beare.

Sheku broke into a winning smile. “I’d be delighted!”

Justin Pearson

General Manager and Artistic Director, National Symphony Orchestra (UK)